In 1866, a Mr. Buffun sold two lots on the outskirts of the tiny pueblo of Los Angeles to a 48-year-old woman named Biddy Mason, for $250. The land was located on rural Spring Street, roughly between Third and Fourth, an area then just recently plotted on a “Map of the Plains.” Biddy’s daughter Ellen recalled that there “was a ditch of water on the place and a willow fence running around the plot.” This was the first piece of land Mason had ever owned, a remarkable feat for a woman who had spent the first 37 years of her life enslaved. But for Mason, this purchase was just the beginning. By the time she died in 1891, she had amassed a fortune of $300,000 (approximately $6 million today), making her the “richest colored woman west of the Mississippi.” More importantly, Mason had left a legacy of perseverance, compassion, and triumph.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason was born August 15, 1818, most probably in Hancock County, Georgia. Born into slavery, her early life, including her family, is a mystery. By the time she was a young adult she was enslaved in the Mississippi household of a farmer named Robert Smith and his sickly wife Rebecca. Mason tended to Rebecca and the Smith children, and became an expert nurse and midwife. She was also made to work in the fields and take care of livestock. During her time in the Smith household, she gave birth to three daughters—Ellen, Ann, and Harriet.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8061239/Biddy_Mason_portrait_memorial.jpg)

Robert Smith was a man forever in search of a better life and richer farmland. The Smiths were also converts to the new Mormon faith. In 1847, the household began a long trek West to join other Mormons in the new promised land of Salt Lake City. They traveled with a large Mormon caravan through Iowa, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Mason walked most of the way, tending to a flock of sheep, baby Harriet strapped to her back. The Smiths settled in Salt Lake City for two years.

In 1851, the restless Smith again packed up his household and joined a group of Mormons traveling to San Bernardino in the new state of California. In San Bernardino, Smith claimed a patch of land along the Santa Ana River. He got into the booming cattle business, and for a short time met with great success.

During this relatively settled period, Mason made friends with the handful of black people in Southern California who had been enslaved. They included Elizabeth Rowan and the successful livery stable owner Robert Owens and his wife, Winnie. Technically, Mason and her children had also become free the minute they stepped into California. The new California constitution stated that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude unless for the punishment of crimes shall ever be tolerated in this state.” However, lacking options and probably unaware of her full rights, Mason continued to serve in the Smith household.

As tensions brewed between North and South, Smith became increasingly nervous that his “slaves” would be forcibly wrested from his control. He also had a falling out with Mormon leaders in San Bernardino, and once again fell on hard times. In 1855, he took Mason, her daughters, and his other former slaves into an isolated canyon in Santa Monica to keep them from being taken from him. He planned to take them to Texas, hoping to take advantage of a California statute that stated that adults who voluntarily returned to a slave state would again be enslaved.

Mason’s friends in the small black community of Los Angeles sprang into action. According to historian Cecilia Rasmussen:

Freed slave Elizabeth Rowan, who distrusted Smith, sent word to Los Angeles County Sheriff Frank Dewitt that Biddy and the other slaves needed help. Dewitt, aided by wealthy black businessman Robert Owens, rode to their camp and served Smith a writ of habeas corpus. He was ordered to appear in court for “persuading and enticing and seducing persons of color to go out of the state of California.”

To keep them safe, Mason and the other Smith “slaves” were taken to the city jail in Los Angeles. In January, 1856, all eyes were on the courtroom of U.S. District Judge Benjamin Hays as the trial began. Smith claimed that Mason and the 14 other people he had kept in the canyon were “members of his family” who voluntarily offered to go with him to Texas. Although Mason was not allowed to testify against a white person in court, Judge Hays invited her into his chambers, where she gave an entirely different account of what had happened.

“I have always done what I have been told to do,” Mason told the judge. “I always feared this trip to Texas since I first heard of it. Mr. Smith told me I would be just as free in Texas as here.” When the judge explained that, due to a state law, her minor children could not be taken to a state where they could become enslaved, Mason replied, “I do not want to be separated from my children, and do not in such case wish to go.”

On January 19, Judge Hays ruled in favor of Mason and confirmed she was free. “All of the said persons of color are entitled to their freedom and are free forever,” he wrote. He hoped they would “become settled and go to work for themselves—in peace and without fear.”

Now rid of Smith once and for all, Mason and her daughters moved into the Owens’ family home in Los Angeles. Her eldest daughter, Ellen, married the Owens’ son Charles, who she had been courting for several years. Through the Owens, Mason met Dr. John Strother Griffin, a white native Southerner who was impressed with her nursing skills. She went to work with Dr. Griffin as a nurse and midwife, and would eventually deliver hundreds of babies in Los Angeles. In her big black medicine bag, she carried the tools of her trade—and the papers Judge Hays had given her affirming that she was free.

Soon, Mason was “known by every citizen” as “Aunt Biddy.” She was quickly beloved in the dusty town of Los Angeles, which numbered only 2,000 or so residents—less than 20 of whom were black. But her new life was not without heartache—in 1857, her middle daughter Ann died, probably of smallpox.

Both Owens and Griffin were involved in real estate and urged Mason to join them in this solid form of investment. By 1866, she had finally saved enough money to buy the Spring Street property. Ellen remembered that her mother firmly told her family that “the first homestead must never be sold.” She wanted her family to always have a home to call their own.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8061273/Biddy_Mason_family_at_memorial_memorial.jpg)

Mason’s small wood frame house at 311 Spring Street was not just a family home, it became a “refuge for stranded and needy settlers.” She also apparently ran a daycare on the property for working women and allowed civic meetings to be held there. In 1872, a group of black Angelenos founded the First African Methodist Episcopal Church at her house; the church met at the Mason home until they were able to move to their own building. She also continued to invest in real estate, while always making sure to give back. According to the Los Angeles Times:

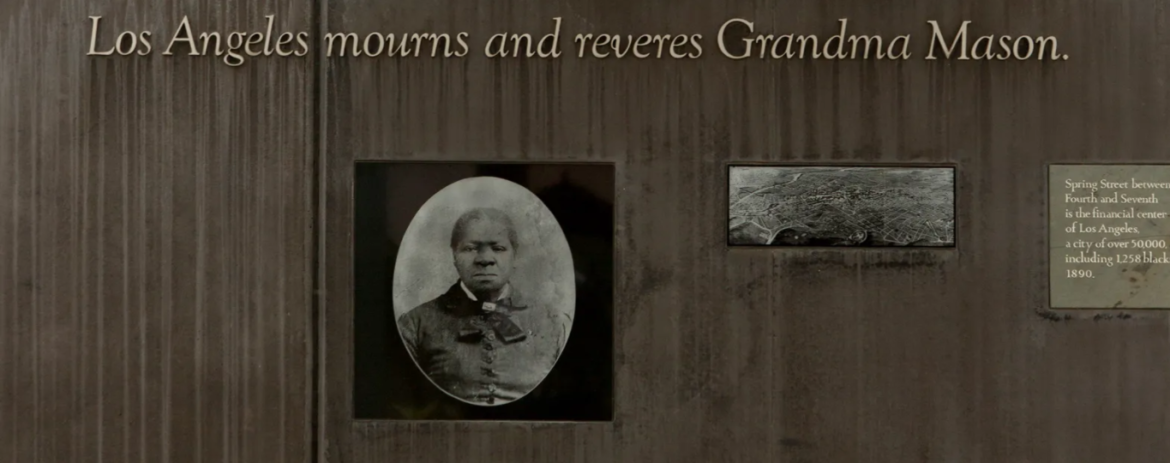

She was a frequent visitor to the jail, speaking a word of cheer and leaving some token and a prayerful hope with every prisoner. In the slums of the city, she was known as “Grandma Mason,” and did much active service toward uplifting the worst element in Los Angeles. She paid taxes and all expenses on church property to hold it for her people. During the flood of the early eighties, she gave an open order to a little grocery store, which was located on Fourth and Spring Streets. By the terms of this order, all families made homeless by the flood were to be supplied with groceries, while Biddy Mason cheerfully paid the bill.

Mason continued as a midwife, eventually setting up her own business. She remained very close to her daughters and their children, insisting that her grandchildren be educated and self-determined. “My grandmother proved my salvation,” her grandson Robert, who became a wealthy businessman and activist, remembered. “She told my father that he could not make a farmer or a blacksmith out of a boy who wanted to be a politician, and she was right.” As a midwife, Mason was able to cross class and color lines—she interacted with a wide variety of Angelenos, whom she looked upon as part of her extended family. A little over a decade after her death, Los Angeles Mayor Meredith Snyder remembered:

Nearly twenty-three years ago, it was my privilege to first meet Biddy Mason, or “Aunt Biddy” as we all loved to call her. I had come from the home of the colored people, and for some purpose, my employer sent me to see Aunt Biddy Mason. The kindly, cheerful greeting of this good soul made me feel almost that I was again at my old home.

Mason was a shrewd businesswoman too. Los Angeles was booming, and rural Spring Street was becoming crowded with shops and boarding houses. In 1884, she sold the north half of her Spring Street property for $1,500. On her remaining half, she built a two-story brick building. She rented the first floor to commercial interests and lived in an apartment on the second. That same year she sold a lot she had purchased on Olive Street for $2,800, a good deal more than the $375 she had originally paid for it in 1868. She also helped her family buy properties around the city. In 1885, she deeded a portion of her remaining Spring Street property to her grandsons “for the sum of love and affection and ten dollars.” She signed the deed with her customary flourished “X.” For although she was a successful real estate pioneer and nurse, she had never learned to read or write.

Mason was so well known in the evolving city that even her business spats were covered by no less than the Los Angeles Times. In 1887, the paper reported on a dispute over a sidewalk:

Biddy Mason had made a contract with David Mulrein to pave the sidewalk in front of her residence. After signing the contract, she got someone else to do the work, for which Mulrein brought action in the justice court and obtained judgement. Biddy appealed the case to Judge Gardiner’s court yesterday, and again fate was against her, so she must pay up.

No doubt, the paved sidewalk had been urgently needed. By the late 1880s, people in need of assistance could be found each dawn lined up in front of Mason’s gate. As she grew old and infirm, and became too ill to see visitors, her grandson Robert was forced to go out to the gate and turn people away. On January 15, 1891, Mason died at her beloved homestead in Los Angeles. “It is not for this property, but her sweet, helpful Christian character that Biddy Mason is remembered,” attorney John W. Kemp declared. “Pioneers all praise her life of good deeds, raising the fallen and helping her race by practical and sterling example. Her life has been an inspiration to many.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8061321/Biddy_Mason_mural_memorial.jpg)

At her death, Mason was one of the wealthiest women in Los Angeles. For reasons never fully explained, she was buried in an unmarked grave at Evergreen Cemetery. In the years after her death, a bitter family feud erupted over her estate; once it was finally settled, the “Mason Block” was put in the hands of her grandson Robert, who became the wealthiest black man in Los Angeles County. The family held onto Mason’s cherished “first homestead” until the Depression.

Over the past 30 years, Mason’s memory has been reclaimed by the city of Los Angeles. In 1988, at a ceremony attended by Mayor Tom Bradley, the First AME Church placed a memorial stone on her unmarked grave. A year later, a memorial in her honor was erected in a small park behind the Bradbury Building near Third and Spring. But perhaps the best memorial to Biddy Mason is her own words, remembered by her great-granddaughter Gladys, decades after her death:

If you hold your hand closed, nothing good can come of it. The open hand is blessed, for it gives abundance, even as it receives.